Generalizing Centipede Game States for Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning algorithms like Q-learning typically find an optimal policy for some Markov decision process by storing and updating a table of values used to map states to optimal actions1. The most interesting MDPs require large or even infinite state-action spaces. It’s intractable in these cases to enumerate and store the entire state-action space in a table. Moreover, many states in a large state-action space are similar and map to the same optimal action. One approach to handling these large spaces is to generalize the state-action space2. A generalization of the state-action space condenses the amount of information needed to learn an optimal policy for the MDP.

I use the Atari game Centipede to illustrate one approach to generalizing a large state space34. The observations in the RGB environment of Centipede are arrays with a shape of \(210 \text{ x } 160 \text{ x } 3\) where each element takes on one of \(256\) distinct values. This setup gives \(256^{210 \cdot 160 \cdot 3} \approx 3.877 \cdot 10^{242751}\) possible distinct observations! We can reduce this massive number by switching to the RAM environment. Now each observation is a one dimensional array of size \(128\) where each element has one of \(256\) distinct values. Still, even using the RAM environment, there are \(256^{128} \approx 1.798 \text{ x } 10^{309}\) possible observations. Constraints of time and space prohibit simply mapping each observation to an action. We need a more condensed representation of the state space. So instead we can develop a generalization of the observations from the RAM environment. Applying Q-learning to this generalization we find a policy that outperforms policies found using larger or random representations of the state space.

Design

There are many approaches to generalizing the state-action space2. We could generalize the entire state-action space. For example, deep Q-learning represents the Q-function with a neural network instead of a table. This representation enables learning an approximation of the entire state-action space using backpropagation. Alternatively, we can generalize the action space (agent’s output) or the state space (agent’s input). Here I choose to build a generalization over the state space.

We also need a sufficient set of state examples in order to learn a generalization of the state space. One way to produce this sample set is to uniformly sample from the entire state space. This method might prove problematic. Uniform sampling generates a sample set that considers each state equally. However, some states are more likely and more important than others. For example, in the Centipede game, states where the centipede is far away from the agent are relatively more likely than states where the centipede is very close. In order to account for these differences, we use empirical sampling. We run the MDP and allow the agent to explore the state space while recording the states it observes. The recorded states are used as the sample set.

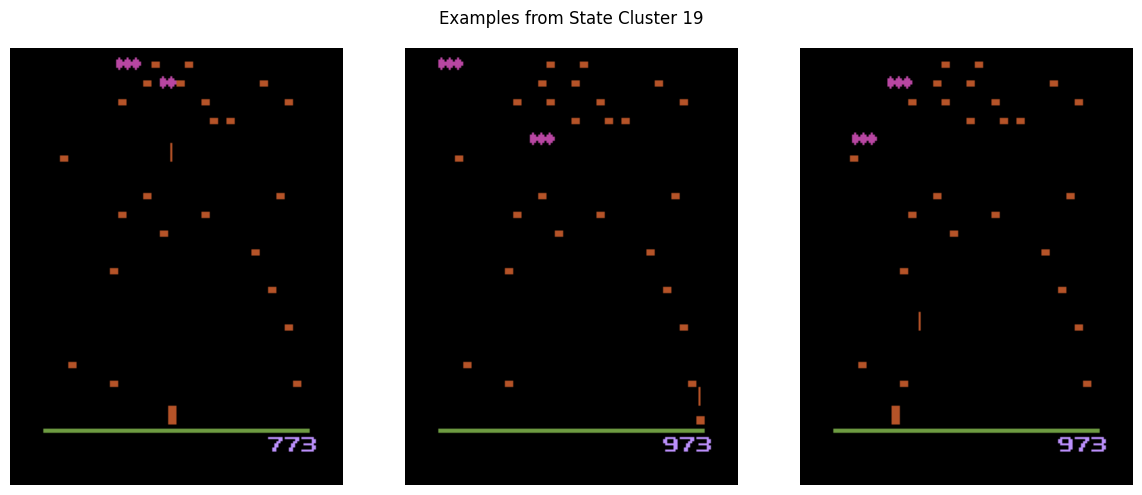

Next, we choose a method to generalize the sample set of observed states. A generalization of the state space partitions the environment into buckets of states that share common characteristics. During Q-learning these buckets represent the same “prototypical” state. A successful generalization partitions these states in a way that suppress unnecessary details while emphasizing the most important. For example, the above observed states from the Centipede environment are grouped into the same prototypical state. Each of these states shared some important similar characteristics, e.g. the centipede is far away and broken into two pieces.

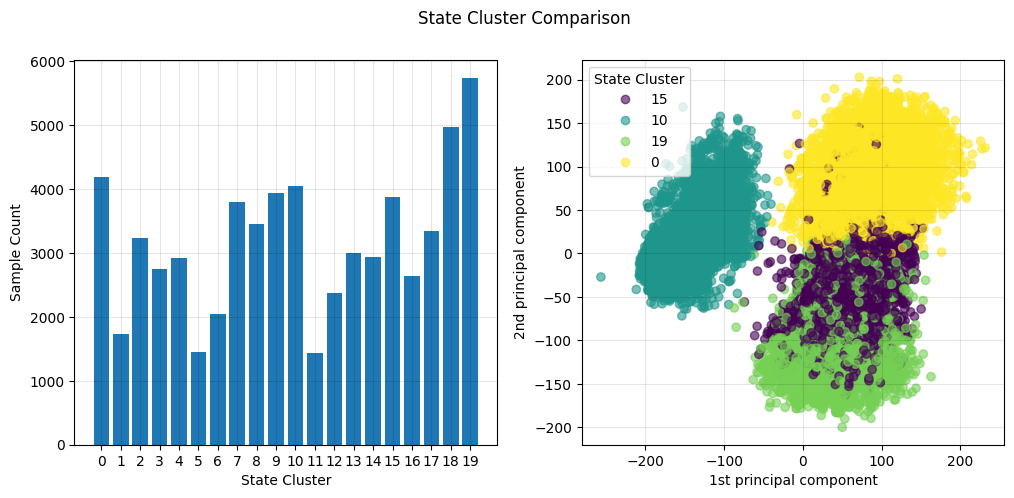

Choosing an appropriate method to find a partition of states depends on what assumptions are made about the environment and the sample set. For example, if the the environment is represented by a vector of boolean valued attributes, a model such as a decision tree might be appropriate for partitioning the states. In Centipede, the RAM environment is represented by a one dimensional vector of integers. Two vectors that are close in value represent similar game states. I chose k-means to find a specified number of average game states to use as prototypical states. The benefit of using k-means is its tendency to create well separated and balanced clusters. For example, clustering states into 20 prototypical states produced fairly balanced clusters. A plot of the first and second principal components also shows decent separation of the clusters.

We also consider the level of granularity of the partition of states. If the partition is too granular, then the generalization will exclude important details of the environment. If the partition is too coarse, then the generalization fails to include important details about the environment. One method is to let the agent learn the appropriate level of granularity during training. This technique is known as adaptive resolution2. Alternatively, if we know something about the environment and the right level of granularity, we can partition the state space prior to training. In the experiments here, I compare two levels of granularity. We partition the state space into 20 prototypical states and 200 prototypical states.

Generalizations of the state space sometimes need to combine supervised and unsupervised methods. In this case, we have a set of prototypical states produced by k-means clustering. However, the agent also needs a way to recognize which of the prototypical states it’s in when it observes a new state. One simple solution is to use k-nearest neighbors model with \(k=1\) to map new states to the nearest prototypical state. k-nearest neighbors is simple, interpretable, and doesn’t require any training. So, the final design is summarized in the sequence diagram The StateMap component is the abstraction that represents the state generalization.

sequenceDiagram

client->>StateMap: build(state_samples, n_clusters=20)

activate StateMap

StateMap->>KMeans: fit(samples, n_clusters)

activate KMeans

KMeans-->>StateMap: cluster centers

deactivate KMeans

StateMap-->>client: StateMap object

deactivate StateMap

client->>StateMap: predict(observation)

activate StateMap

StateMap->>NearestNeighbor: fit_predict(observation, n_neighbor=1)

activate NearestNeighbor

NearestNeighbor-->StateMap: nearest prototpyical state (cluster center)

deactivate NearestNeighbor

StateMap-->>client: state

deactivate StateMap

Results

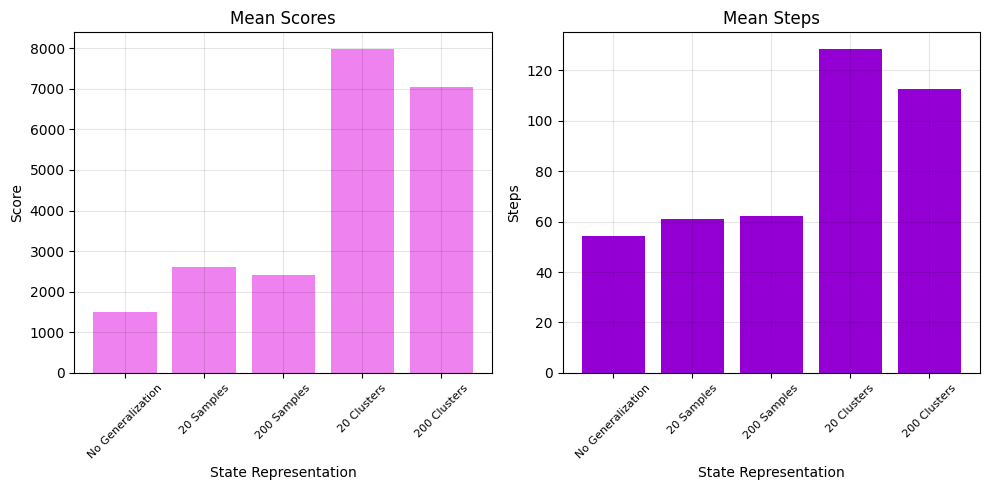

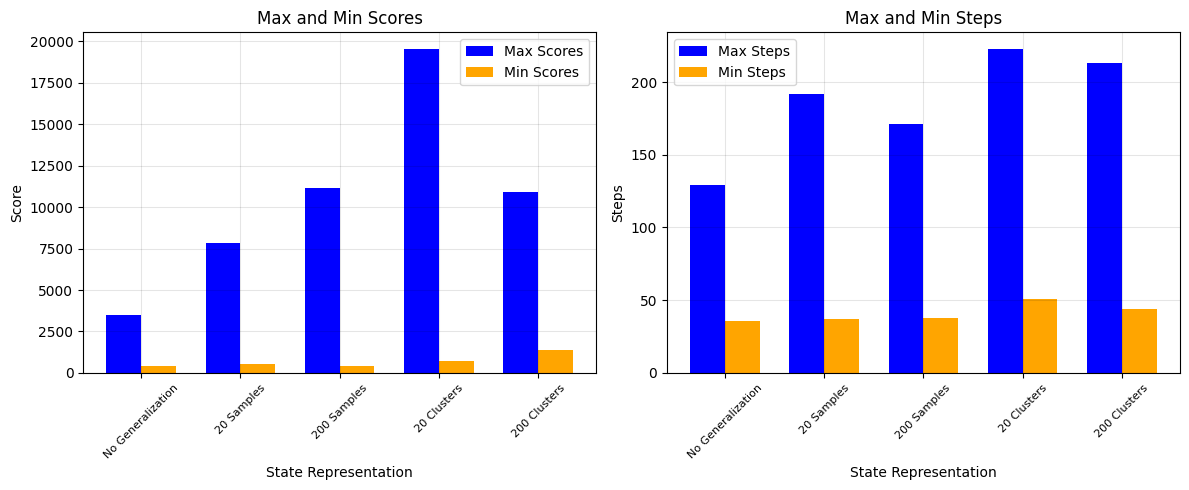

In order to see how state generalization improves Q-learning, consider 5 different learners each trained on a different representation of the state space for 5 runs of 1000 episodes. The results are in the bar graphs. The learner trained on the entire state sample set performs worst. The large state space makes it difficult for the learner to find an optimal policy given the training constraints. The learners trained on a random sampling of states from the sample set performed slightly better. These learners find optimal actions for the sample states, but those states don’t capture many important properties of the Centipede environment. So, finally, the learners trained using the state generalization based on the clustering far outperform the other learners.

There’s also some interesting differences in the performance of the agent using the 20 cluster generalization versus the agent using the 200 cluster generalization. The 20 cluster agent achieves the highest average and max scores. So, even when accounting for a relatively few number of states, generalizing the state space significantly improves the performance of the agent. Also, given that part of the objective of Centipede is to survive, the longer episodes of the 20-clusters agent suggests it learned a better policy for evading threats. The 200 cluster, however, achieved the highest minimum score. The more granular generalization helped the agent identify more scoring opportunities than 20 cluster agent.

Conclusion

The approach to state generalization described here is simple and straightforward. There’s many ways we could make it more sophisticated. One possibility would to tune k-means clustering against a metric like the silhouette score to find an optimal number of prototypical states. Another possibility is that slight, important variations among states require the agent to react differently. We could account for this by using k-nearest neighbors with more than one neighbor. One more possibility is to use dimensionality reduction techniques such as principal components analysis to identify the most significant features of the state space before clustering. Still, the principle demonstrated by the above results remains the same. We can turn MDPs with large or infinite state-action spaces into tractable problems for learners by finding a decent generalization of the state-action space.

The code for the experiments can be found on github.

References

Barto, Andrew G., and Richard S. Sutton. “Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction.” MIT Press, 2018. ↩

Kaelbing, L. P., Littman, M. L., & Moore, A. W. “Reinforcement Learning: A Survey.” Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 4 (1996), 237-285. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

Machado, M. C., Bellemare, M. G., Talvitie, E., Veness, J., Hausknecht, M. J., & Bowling, M. “Revisiting the Arcade Learning Environment: Evaluation Protocols and Open Problems for General Agents.” Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 61, 523-562 (2018). ↩