RuleRover: A Logic Programming Library in Ruby

Motivation

RuleRover is a Ruby gem I’ve built to implement some of the fundamental logic programming algorithms detailed by Russell and Norvig1. My interest in this field traces back to my graduate studies in philosophy of mind and early AI, where I first encountered the concepts of symbolic AI. This approach, which represents knowledge and reasoning using symbols and rules similar to those in first-order logic, caught my attention as a potential model for how the mind works. Of course, there many critics of this model of the mind that claim it fails to intuitively explain common mental phenomena (I’m thinking of the Chinese Room thought experiment). But I’ve always found it fascinating and, to some degree, intuitively plausible.

This academic interest took a practical turn when I started teaching first-order logic and found myself facing hundreds of student proofs to grade. At the time, I knew next to nothing about coding, but I was familiar with the basic concepts. I figured it should be straightforward to whip up a simple Python script to check my students’ proofs for errors in applying rules of inference and translation. After all, both Python and first-order logic are formal languages – how hard could it be to use one to express the other? As it turned out, quite hard. That initial project never quite got off the ground, but the idea stuck with me. RuleRover is my attempt to finally scratch that itch and bring that unfinished project to life.

Design and Implementation

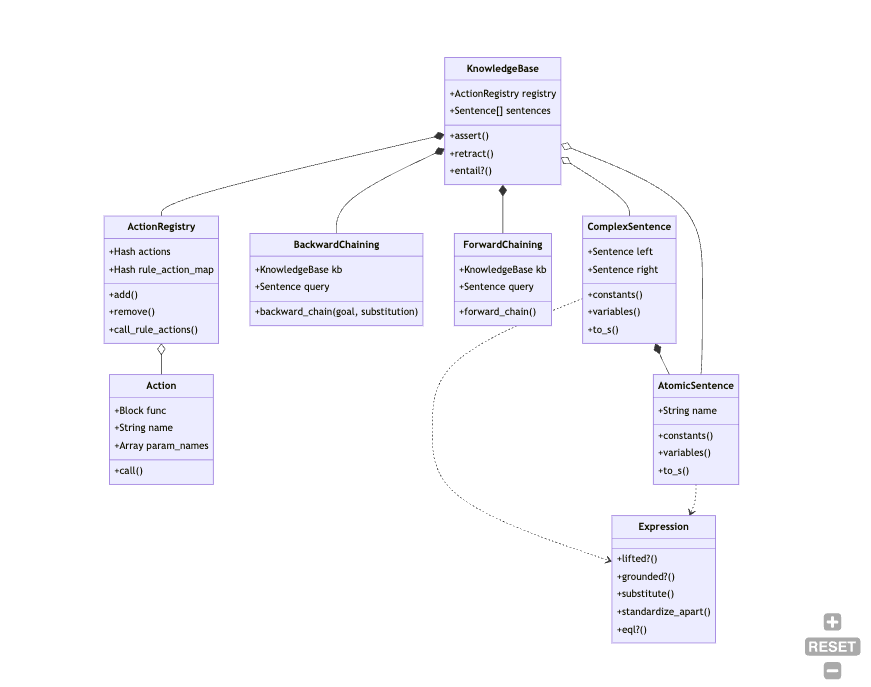

At its core, RuleRover is designed as a simple yet expressive domain-specific language (DSL). This DSL provides an interface to the KnowledgeBase class, which is the core component of the system. Think of the KnowledgeBase as a container for all the logical sentences our system knows about. Users can assert new facts, retract old ones, and query the system to see what it can deduce from its current knowledge. The following breaks down the key components that make this possible.

The Expression mix-in is the component that gives every sentence in our knowledge base its fundamental behavior. It defines how sentences are represented and manipulated within the library. The Expression mix-in does a few crucial things: it ensures all sentence classes share a common interface, checks whether an expression is fully instantiated (what we call “grounded”) or contains variables (“lifted”), handles variable substitution, and standardizes variables to avoid naming conflicts.

Atomic expressions are the building blocks of first-order logic: predicates, functions, constants, and variables. Each atomic sentence has a name and keeps track of the constants and variables it contains. They also know how to turn themselves into strings, which comes in handy for displaying or processing them in different contexts.

But the most interesting statements in any logic are complex. The ComplexSentence class handles these more sophisticated logical relationships, like conjunctions (“and”), disjunctions (“or”), conditionals (“if-then”), and biconditionals (“if and only if”). A ComplexSentence is made up of two sub-sentences (left and right) and, like its simpler cousins, it can tell you about the constants and variables it involves.

RuleRover is able to answer queries about what the knowledge base entails using forward and backward chaining. BackwardChaining is like a detective working backwards from a crime. It starts with the query and works its way back, trying to find facts or rules that support it. ForwardChaining, on the other hand, is more like a gossip spreading through a network. It starts with known facts and applies rules to infer new facts, continuing until it either proves the query or runs out of new things to say.

Backward chaining also incorporates an ActionRegistry. The ActionRegistry allows us to link actions to specific rules in our knowledge base. When the conditions of a rule are met, the corresponding action gets triggered. This feature is crucial for systems that need to do something tangible based on logical inferences, not just answer true or false questions.

Conclusion

Logic programming isn’t just a set of algorithms; it’s a philosophy about what intelligence takes. At the moment large language models are in the spotlight, but there’s still something compelling about the clarity and rigor of symbolic AI and formal logic.

Alexander Hamilton once quipped that “man is a reasoning rather than a reasonable animal.” I think this captures a key insight. We can aspire to think rationally, but thinking is not inherently rational. Rather, we have to think in a certain way. And algorithms like forward and backward chaining on definite clauses mimic this ideal mode of thinking that’s clear, precise, and rigorous. These qualities, in my view, represent a pinnacle of human cognitive potential - or at least one facet of it.

Of course RuleRover is an experimental library and definitely not production-ready. But there’s plenty of production-ready logic programming languages available. For example, in the ruby community there’s the Wongi::Engine gem that implements the Rete algorithm which is an efficient form of forward chaining. Or, there’s Prolog which implements an efficient form of backward chaining and has been around since the 1970s.

The RuleRover gem can be found here and a simple example here. I’m always looking for feedback and collaborators. If you’re interested in symbolic AI, logic programming, or just want to chat about the philosophy of mind, feel free to reach out.

References

Russell, S., & Norvig, P. (2021). Artificial intelligence: A modern approach (4th ed.). Pearson. ↩